Should PhRMA Acquire 23andMe?

The Market in Personalized CAGT May Depend on It

In November last year, about two months before all the selfies from JPM 2024 began flooding the zone, UK Biobank debuted the world's most comprehensive health data source derived from half a million people's whole genome sequences.

The content it holds is derived from 500,000 volunteers who shared a deep dive into their lives over 20 years. More than 10,000 variables were collected on each, giving capitalists and academics extraordinarily rich data to mine. According to The Guardian’s coverage of its official unveiling on November 29, 2023, more than 30,000 researchers worldwide are registered to access the data. These researchers have published more than 9,000 academic papers. Today, writes the newspaper, “the UK Biobank ranks as the world’s most important health database and is arguably the UK’s most significant scientific asset.”

UK Biobank positions itself as a public good to enable scientific discoveries and improve human health. Per the website, this abundance of genomic data is unparalleled, but what cements it as a defining moment for the future of healthcare is its use in combination with the existing wealth of data UK Biobank has collected over the past 15 years on lifestyle, whole body imaging scans, health information, and proteins found in the blood. "This is a veritable treasure trove for approved scientists undertaking health research, and I expect it to have transformative results for diagnoses, treatments and cures around the globe,” said Professor Sir Rory Collins FRS FMedSci, Principal Investigator, UK Biobank.

Presumably all those “transformative” diagnostics, treatments and cures will be made to happen through products and services — i.e., markets developed through marketing and sales — within the context of a commercial model, as a business that earns revenue and turns a profit.

And it's probably a safe bet that Google Deepmind drug-development spin off Isomorphic Labs uses Biobank data for the AI platform that resulted in a $3 billion deal with two of the largest drug companies in the world, Eli Lilly and Novartis. Isomorphic Labs is part of herd of disrupters and transformers, one over 460 AI startups currently working on drug discovery. Globally, more than $60bn has been invested into the space so far, and the funding flood isn’t showing any signs of letting up.

Isomorphic Labs expects testing on its first AI-designed drugs to begin this year, as tech startups race to turn algorithmic magic into actual treatments.“We’ll hopefully have some AI-designed drugs in clinical trials by the end of the year,” the firm’s Nobel Prize-winning CEO Demis Hassabis told a panel at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January. “That’s the plan.”

The technical potential of AI-powered drug discovery is huge. At least on paper.

Instead of spending decades testing chemicals by hand, machine learning algorithms can sift through mountains of data to spot patterns and predict which molecules could make the next miracle drug. This could lead to faster drug development, cheaper costs, and new cures.

But it’s the sound of one hand clapping.

Missing from all the keynotes, investor presentations, VC pitches, podcasts and fireside chats at all the panel discussions and healthcare conferences and Davos-like gatherings is strategic imagination around provenance, and the untapped value of ‘data equity’ as an engine for big growth and economic development.

On The Origin of Things

The uncomfortable conversation that’s arrived for the pharmaceutical-as-healthcare / healthcare-as-pharmaceutical market is this:

Can you (i.e., industry) get to run-state faster by sharing the wealth from all those new health products and markets developed from the data that comes through their (i.e., everybody else ‘out there’ in the ether somewhere) sustained and infinitely-expanding engagement with digital content, which also includes the roughly 137 terabytes of data generated every day when the collective we -- consumers-as-patients; patients-as-consumers; HCPs-as-consumers; everybody-as-technologists -- interact with the entire health apparatus in its current form?

Should those 500,000 people whose data is in UK Biobank get a cut of revenue (sales or taxes) from markets based on their data?

If you ask the family of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman who had cells taken from her and used for research without consent more than 70 years ago, the answer is yes. They successfully sued JP Morgan attendee Thermo Fisher Scientific, which earned billions from products and services derived from her cells, for exactly that reason. Terms were not disclosed, but the legal team for the family is promising more.

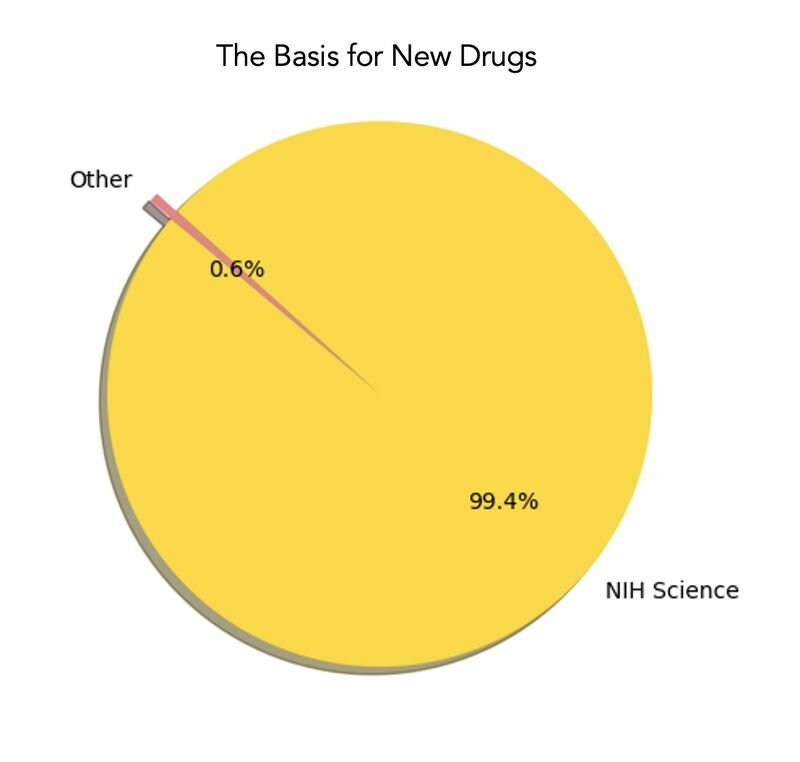

If you ask the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, who are using the provenance of drugs in their negotiations with the pharmaceutical industry as part of the IRA, the answer is also yes. Among the factors CMS will consider for “the purposes of negotiating a maximum fair price for each of the selected drugs” include “prior federal financial support for novel therapeutic discovery and development with respect to the selected drug.” In other words, did taxpayers help fund drug development and commercialization with taxpayer health data, perhaps as part of an NIH study (the National Institutes of Health contributed $187 billion for basic or applied research related to the 356 drugs approved 2010–2019, nearly all of which were subsequently launched by biopharmaceutical companies).

Comparison of Research Spending on New Drug Approvals by the National Institutes of Health vs the Pharmaceutical Industry, 2010-2019; JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(4):e230511.

Perhaps those taxpayers were also military veterans of the United States — there are more than 16 million, of which around 35,000 are homeless — who were part of a clinical study enabled by the VA’s Million Veteran Program.

According to the VA, the Million Veteran Program is the largest such database in the world. It includes not only genetic information but also is linked to the department’s electronic medical records and even contains records of diet and environmental exposure. The VA says its data are available for now only to V.A. doctors and scientists, most of whom also have academic appointments. These academics, the VA is proud to point out, have published hundreds of studies based on data that has already been collected from veterans.

Which is notable not because any of this scientific content is actually read by real people and turned into some sort of clinical practice improvement to scale better care for veterans. It’s notable because this scientific content is now available for reading by the large language models being developed by Google, Microsoft, Datavant, Epic, Truveta, Meta and many others, who in turn position them as their humanity-saving visions (for more Blue Spoon thinking on this, see How to Sell AI in the Kingdom of the Bored).

It’s a weird feedback loop that seems to discard, omit or assume-way the one thing these models/markets will soon need more than anything else: more data from human beings. Big Tech may soon reach Peak Data.

“We could run out of data to train AI language programs, forcing researchers to get creative to make training data stretch further,” writes Tammy Xu in MIT Technology Review. In recent years, the trend has been to train these models on more and more data in the hope that it’ll make them more accurate and versatile.

“The trouble is, the types of data typically used for training language models may be used up in the near future — as early as 2026, according to a paper by researchers from Epoch, an AI research and forecasting organization. The issue stems from the fact that, as researchers build more powerful models with greater capabilities, they have to find ever more texts to train them on. Large language model researchers are increasingly concerned that they are going to run out of this sort of data, says Teven Le Scao, a researcher at AI company Hugging Face, who was not involved in Epoch’s work.”

Which is exactly what’s bothering the media outlets and publishers the world over.

They are suing ChatGPT-owner OpenAI over claims their copyrights were infringed to train their systems. The lawsuit by the New York Times in particular, which also names Microsoft as a defendant, says the firms should be held responsible for "billions of dollars" in damages because readers can get New York Times content without paying for it -- meaning it is losing out on subscription revenue as well as advertising clicks from people visiting the website.

In his book “Who Owns the Future?” American computer scientist Jaron Lanier, who was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by TIME magazine and is now a Microsoft employee, makes the case that people should own their data and be compensated if they choose to share some of it.

“No one disputes that big data can be an essential tool in medicine and public health,” he says. “Information is by definition the raw material of feedback, and therefore of innovation. But there is more than one design for integrating big data into society. Because digital technology is still somewhat novel, it’s possible to succumb to the illusion that there is only one way to design it. Is it conceivable to use big data in such a way that people and their economy get healthier?”

Until recently, our global economy was basically powered by two forms of value exchange: the first was based on the exchange of goods and services, and then later, the exchange of attention in the form of media and entertainment. Now we have to add a third construct: data equity. This is data that amplifies, informs and powers the commercialization strategies of entire industries and infrastructures, economic systems and subsystems — this includes $100 billion markets for electronic health records, pharmacy benefit management services, employee benefit consultants, data brokers, drug development and marketing, commercial health insurance, technology services, venture capital, and media and content.

Not to mention government revenue. (For more Blue Spoon thinking on this, see Can Novartis Save the NHS?

On "Maximizing the Value” of Things

23andMe filed for bankruptcy late last night. Anne Wojcicki, its CEO, announced her resignation, completing the strategic collapse for the DNA-testing company. Wojcicki said in a late Sunday post on X that she still aims to buy the company’s assets. “I remain committed to our long-term vision of being a global leader in genetics and establishing genetics as a fundamental part of healthcare ecosystems worldwide,” she wrote.

The company said its chapter 11 filing in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Missouri is “the best path forward to maximize the value of the business.”

More than 15 million people provided the company with their DNA samples, a virtually unprecedented repository of human genetic information that could be sold in bankruptcy proceedings.

23andMe never solved its central business problem, which is the same business problem that the strategically-collapsing retail pharmacy market has never solved: ‘continuous health engagement’. Customers only need to take its DNA test once. It tried alternative, albeit Standard Model, business strategies, including selling subscriptions, but those never caught on. It also sought to license its data to outside pharmaceutical companies to help with their drug-development efforts. But there, too, it struggled to find significant recurring revenue.

From the Wall Street Journal’s reporting this morning:

The company’s prior board resigned en masse last fall, saying that they had not received an “actionable” buyout proposal from her and that they differed with her over the strategic direction of the company. The company’s current board rejected another offer earlier this month.

23andMe had achieved an enterprise value above $6 billion shortly after going public in 2021. Today its enterprise value is around $0—the cash on its balance sheet roughly equal to its market capitalization.

Last year, The Wall Street Journal reported on 23andMe’s struggle to find a profitable business model as its ambitious bet to develop drugs using its stockpile of DNA faced expensive, lengthy delays.

Wojcicki pressed ahead, launching a subscription business offering personalized health reports, lifestyle advice and unspecified “new reports and features as discoveries are made” for an initial $229. She also bought a struggling telehealth company.

Sandy Pound is the Vice President and Chief Communications Officer at Thermo Fisher, who presented at JP Morgan. She sat down for a brief interview with her public relations agency to produce a piece of Q&A content based on her thoughts about “why you should embrace being uncomfortable as a communicator” – two excerpts seems salient here:

What communications challenge keeps you up at night?

“Before the pandemic, the biggest challenges were company issues which required traditional crisis communications. We had a robust approach to handling crises through tested scenarios and a playbook of actions. Since the pandemic, the world has been a very different, and at times, difficult place. The unexpected external events that we might face cause me the most concern.”

What is the best advice you’ve ever gotten?

“If you’re not uncomfortable, you’re not growing. This isn’t exactly what I wanted to hear from my husband any time I share something that makes me uncomfortable, but he is 100% right and I appreciate his honesty. It’s easy to fall into a pattern and as communicators, I think we need to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.”

Who ultimately owns the data around which very, very large amounts of money are being made? And could we reshape the economics of a digital society — and scale the technical potential of personalized medicine — where there was a fairer treatment of the value of one’s data?

The thing industry and government should probably start having an uncomfortable discussion around is how to make the invisible hand visible — not in the corporate sponsorship of the White House Easter Egg Roll sort of way — but to begin seeing ‘data equity’ as something that can unlock a whole new form of wealth and economic competition, taking dealmaking between industry and government to a whole new level. [Rather than taking a chainsaw to the VA, perhaps a modern strategy for Musk would start by asking Google et. al. if it’s using any VA data to train its LLMs If so, then what follows are questions about reinvesting some earnings into helping state and local governments care for homeless veterans. (For more Blue Spoon thinking on this, see What’s the Business Value of the VA to Eli Lilly?)]

You can either get in front of this emerging theme and shape it to your advantage, or sit back and hope for the best, becoming a victim of it in a sort of perpetual state of disbelief, the Giant Waves of Disruption drowning you as a steady-breaking set of Big System Shocks that seem beyond normal comprehension to define, much less ride successfully to shore.

Across the arc of human experience, entirely new economic systems worth hundreds of billions are there for the inventing, yet we're stuck defending the past with obsolete arguments and understanding about "value" and “cost”.

Big System Innovation First, Big Technology Innovation Second

The future belongs to those brands that define the rules by which others have to play.

It's about building and operating the most inviting and empowering networks, and winning new subscribers with integration models that deliver what people really want: predictable and unhindered access to the goods and services they, and their data, have had a hand in bringing to market.

Perhaps it’s something 23andMe should have considered as a way of making new money — for itself, for its shareholders, and for the millions of people contributing data to its now bankrupt business.

Perhaps it’s the kind of industry-level solution the drug market should creatively consider to deliver on big system innovation, a different ‘storyline of value’ around the promise of technical potential for the stalled cell and gene therapy market, one that analysts forecast should be worth around $177 billion to the pharmaceutical industry by 2034....at least on paper.

A modern strategy starts with different questions.

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon, the global leader in positioning strategy at a system level. Blue Spoon specializes in constructing new industry ecosystems.