Can Big Pharma Save Big Food?

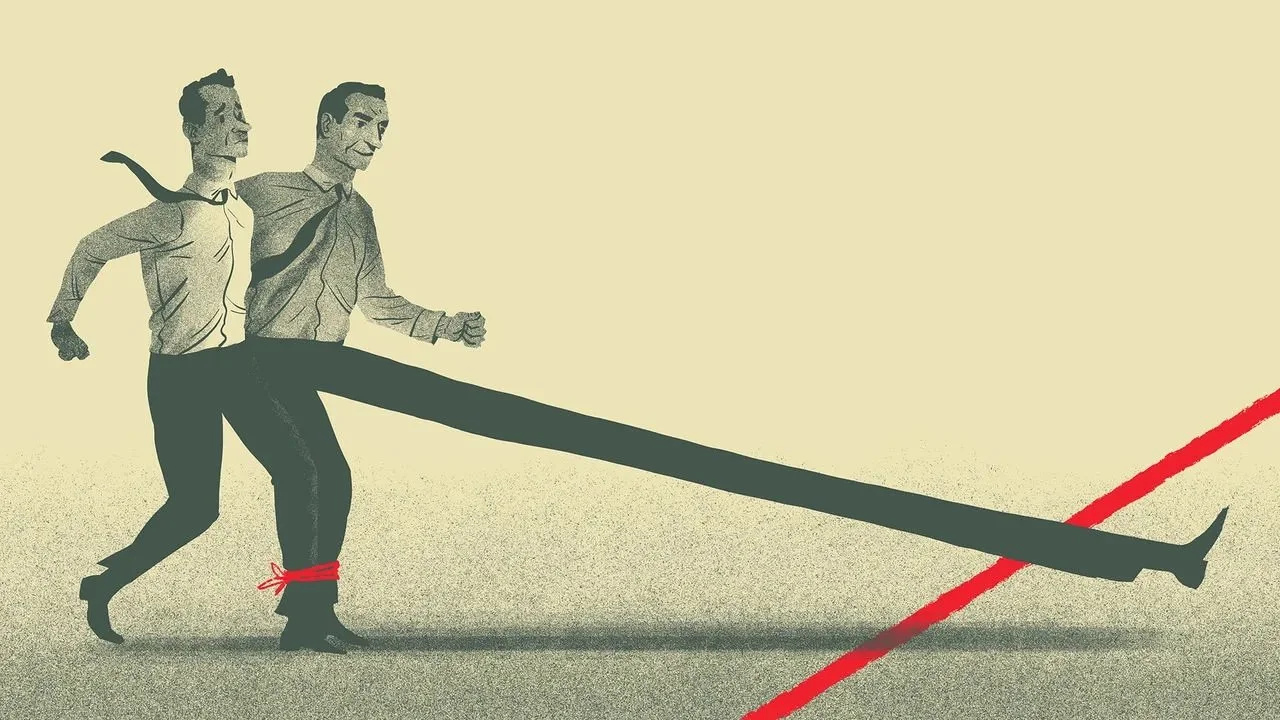

The Era of Monovation is Over

Takeaway: Two markets cohering and co-creating as a system will over the long run outperform any one market acting alone.

**********

“The follow-on health benefits from patients losing weight are rippling across industries. Diet and exercise companies, such as Weight Watchers, have called Ricks seeking advice on how they can win in a market where GLP-1 drugs are booming. He’s also fielded calls from corporate leaders who have questions about these drugs’ impact on their businesses.

“Of course we talked to Walmart and all our big food stores,” Ricks said. Last year, Walmart’s U.S. CEO, John Furner, told Bloomberg News that shoppers who picked up prescriptions for GLP-1 drugs at Walmart pharmacies were putting less food in their grocery baskets.

Ricks advises the affected companies to adapt to a world where fewer consumers are obese. “If you make knee replacements? That’s not great. But I’m sure there’s other health problems they can go work on and make devices for,” he said. “We will directly displace those things. That’s not our strategy, but we are trying to make it better and easier to live with those conditions by losing weight.”

Likewise, Ricks says foodmakers will need to adjust. “If they’re worried about salty snack foods high in fat, saturated fat, or selling less? I’d say, ‘Well, why don’t you make healthier ones?’ ” he said.

—- Lilly’s Weight-Loss Drug Is a Huge Hit. Its CEO Wants to Replace It ASAP. Wall Street Journal, June 13, 2024

You can’t argue with massive success.

Earlier this month Lilly reported earnings for the second quarter. Its mushrooming GLP-1 franchise, Mounjaro and Zepbound, blew past estimates allowing Lilly to increase its revenue outlook for the year by $3 billion. Its stock performance (up more than 220 percent in less than three years) is on an eye-watering run, with Bank of America projecting its share price to climb past $1150 based on its progress in obesity, Alzheimer’s and diabetes, where yesterday Lilly reported that tirzepatide cut the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes by 94% in prediabetic adults.

Novo Nordisk is no slouch either.

The first half was also a strong one for its competing GLP-1 business, with Ozempic and Wegovy having grown by 36% and 74%, respectively. Its stock performance is on the same trajectory as Lilly’s, up almost 150 percent in less than three years. And as Novo continues to invest in more capacity and data to roll out the treatments and promote their benefits to more markets and more patients, the space for growth will continue to expand for everyone.

Arguably the best case study to predict how the $100 billion market in GLP-1s will all shake out is the statin war waged between Pfizer vs. Merck vs. BMS vs. AstraZeneca more than 25 years ago (for an introduction, check out Statin Wars: The Heavyweight Match — Atorvastatin versus Rosuvastatin for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis, Heart Failure, and Chronic Kidney Disease). Lipitor, which was introduced by Pfizer back in 1997, is expected to be the drug with the third highest lifetime sales at the end of 2028. As of end-2022, the cholesterol-lowering drug aggregated lifetime sales of $172 billion, which is expected to increase for some additional six billion dollars until 2028.

The statins in the late 1990s, like the GLP-1s now almost three decades later, are an example of the ‘rising tide model’ of drug development and commercialization, in which all the pharma boats ride the crest of one big new wave. And this is pretty much how pharma has been operating and thinking about competition for the past 100 years, particularly in chronic disease.

A “Radically” Different Strategy Story

Earning $172 billion is a strong data point to prove out an operating philosophy. And the global market in statins is still growing, expected to surpass $22 billion in the next five years.

But could the ‘statin market’ have been even bigger and more opportunistically diverse if the business was managed with different foresight, evolved collaboratively with another set of ‘non-traditional partners’ — i.e. retail pharmacies and their suppliers of food products and groceries — all sharing marketspace, all aligned within the context of a better care and service infrastructure than the mass of administrative complexity we have today?

Would it have been possible for that new infrastructure to have a roadmap that integrated a ‘specialized EHR market’ into the mix, thus changing the practice of medicine?

Could that infrastructure, once established, now be leveraged to degrade the power and control of Big PBMs, or displace them entirely, transforming the economics of the drug market as a whole?

Would it be possible to use that infrastructure to create growth and innovation for a collection of markets that rotate around the drug market and depend on it for success, including the now crumbling retail pharmacy market, the soon-to-be-sued employee benefit consulting market, the primary care market that Walgreen’s and Walmart just abandoned, and even the overhyped digital health markets, which have yet to deliver much beyond a cool tech pilot with technical potential?

And based on the ‘process knowledge’ gained from learning how to construct an industry ecosystem from scratch, would the pharmaceutical industry now be better positioned to approach the GLP-1 space not as a $100 billion drug market per se, but a $440 billion system of markets collaborating and competing on the ‘production of cardiometabolic health’ (you can access that ecosystem concept here on the Blue Spoon downloads page)?

And could the ‘production of cardiometabolic health’ be used as a more original frame for health policy making, one where the pharmaceutical industry collaborates with the food industry to shape better industrial policy, a completely different innovation agenda for the country conceptualized collaboratively with the federal government?

Big Food (the ten most valuable packaged-food and soft-drink companies have a combined market capitalization of around $1 trillion; average operating margin last year was around 17 percent) is, like UnitedHealthcare, nearing its own tipping point, a set of systems converging on its business model, self-organizing into a bigger force than itself, with the resources and the staying power to transform the industry. In order to jump to its next growth curve, it will have to craft a more unique strategy story, one that changes its relationship with government, elevates the concept of ‘market access’ as part of brand planning, and intentionally engages with the global healthcare industry (currently valued at approximately $9 trillion, depending on how you define its boundaries).

Writes The Economist last week (see: Can big food adapt to healthier diets? It must contend with weight-loss drugs and concerns about processed foods):

“The industry faces threats. The impact of its products on the health of those who consume them has long concerned shoppers and policymakers alike. Consumers may now indulge in them less as weight-loss drugs become cheaper and more convenient. What is more, a growing body of research suggests that it may not only be an excess of sugar, fat and salt that causes health problems, but also the heavy processing used to whip up cheap nibbles.

Both threats could reshape the industry — and transform what the world ingests.”

The art of modern leadership, in business as well as in government, is the skill to see tipping points before they happen, to prevent strategic collapse. You want to create history rather than simply being swept along by its currents. For big market innovation — the kind that moves the needle on companies the size of UnitedHealthcare or Eli Lilly or Coca-Cola, the question for strategy is how to get in front of change rather than become a victim of it. In other words, how to reshape rather than getting reshaped.

Mark Schneider, Nestlé’s chief executive, was pushed out of the company last week, learning he would be losing his job just 24 hours before it was announced publicly. On an investor call on Friday morning, according to the Wall Street Journal, Nestlé veteran Laurent Freixe, the incoming CEO, talked about how he wanted to improve market share and productivity, raising eyebrows among some analysts who said the ideas, while sound, weren’t in any way new.

“While we absolutely understand that he will not have had much time to gather his thoughts, his priorities around market share and sales growth, investment in the business and productivity savings do not sound radical,” said RBC analyst James Edwardes Jones after the call had ended.

Underscoring this point:

The probability for big commercial success for a business locked in the conceptual past is low. Ditto for its business managers

Helping Walmart (and Nestle) Innovate

If you think of "drug" as having untapped power to bring market fragments together -- having 'positional value' as a keystone to construct and cohere entirely new industry ecosystems -- then you compete radically differently, as a system.

The cocktail of additives and preservatives in ultra-processed foods (UPFs) harm people in ways both known and unknown. Calorie-rich but usually nutrient-poor, UPF contributes to obesity in part because its palatability and soft texture foster overconsumption, overriding satiety signals from the brain. It seems to affect the gut microbiome, the trillions of bacteria that contribute to health in a range of ways.

So if the objective is using GLP-1s to make a supersize impact in the business and economics of healthcare worldwide, then one thing that will spark and sustain that is a set of equally big markets collaborating with GLP-1s on primary prevention, a market set that integrates and innovates the market for groceries and nutrition and healthcare technology, among many others (Walmart reported more than $264 billion in grocery sales last year, about 60 percent of its business, hence the call to Lilly).

So, for example, Novo Nordisk + Walmart + Nestle + Fortrea collaborating on shared marketspace — inventing the data and the specialized cognition to produce the science of not just personalized cardiometabolic health, but a personalized shopping experience around personalized cardiometablic health — will beat Eli Lilly operating and investing in drug science and drug promotion alone.

On the other hand, if the goal is industry level change, to reshape the operating environment in your favor, to literally transform the practice of medicine around the ‘production of cardiometablic health,’ then Eli Lilly + CVS Health + Unilever + Oracle Health will beat AstraZeneca acting and operating in its silo.

And different still, Roche + DexCom + General Mills + Springbuk will beat Amgen, not in the race to get another GLP-1 to market per se, but in a whole new game that bypasses OptumRx and CVS Health altogether, targeting self-funded employers directly and with a more original storyline of value.

Everything is in the remix.

"We think actually over time this is going to be a four-to-six-horse race because right now you only have one device which is injectable going after one treatment, which is weight loss. But we're seeing innovation in parts of the market where we're looking at people looking at oral instead of injectable. People are looking at applications beyond weight loss," Tema ETFs founder and CEO Maurits Pot told Yahoo Finance last week.

Which isn’t a particularly novel insight.

Every drug in every category since time immemorial runs a race where more than one horse competes. The question for really big market innovation is this: what kind of race do you want to run, and do you want to run it alone?

The map to a sustained edge is to do something a competitor can't.

So if you bound strategic thinking conventionally, positioning your commercial model as competing in the obesity 'drug market' -- say Eli Lilly vs. Novo Nordisk vs. AstraZeneca vs. Roche vs. Pfizer vs. Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals vs. Viking -- then your roadmap quickly and invariably leads to competitive convergence. This is a place of maximum congestion, a traffic jam of sorts, where price and hyper-commoditization become defining features of ‘the market’ in which you play, and in which others understand and assess your value.

It’s a frame of reference that has brought pharma to where it is today re: negotiating with the federal government via the Inflation Reduction Act, despite the industry’s two-decade, multimillion-dollar lobbying campaign and barrage of lawsuits to stop them (Ozempic and Wegovy could be eligible for negotiation next year, according to Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the Program on Medicare Policy at KFF. Lilly’s Trulicity may follow in 2026)

Novo Nordisk CEO Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen says the company is expecting solid performance in the coming months.

“We’re very confident in our ability to scale and also supply patients and deliver now stronger growth for the second half. So I say worry less about what happened specifically in [the second quarter], there was some adjustments to rebates etc, look at our guidance and we believe there’s a very attractive growth in front of us,” he told CNBC’s “Street Signs Europe.”

Jørgensen said that early trial data from Roche may attract attention, but he was still very confident that the company could “sustain competitiveness long term.”

I suppose that comes down to how one defines “competition”.

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon, the global leader in positioning strategy at a system level.